How the Apple Archive Ended Up at Stanford

The Real Story

Anna Mancini is a retired corporate librarian and archivist. As a librarian at Apple in 1997, she managed the donation of the Apple Archive to Stanford University.

Lately I’ve been reading about the Apple Archive at Stanford in the news, and a couple of things have really bothered me.

First was a comment almost tossed off in Charles Petersen’s August 8, 2021 article on Substack. He was doing research in the Stanford Archives because, he wrote:

I planned to spend a month looking at the vast collection of Apple’s records that Steve Jobs had sent over when he returned to the company in 1997 and decided the new Apple he intended to build would be so forward-looking it could get rid of its museum.

(Italics mine.)

“Hmm,” I thought. “I wonder where he got that information.”

I let it go, for the moment. But then I read the New York Times article about Laurene Jobs starting the Steve Jobs Archive. Here’s what that article said.

When Mr. Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, a dozen years after he was forced out, one of the first things he did was offer Stanford University the company’s corporate archives, said Henry Lowood, the curator of Stanford libraries’ History of Science and Technologies Collections. “Stanford had a signed document from Apple’s legal department within 24 hours, allowing it to transport some 800 boxes from the company’s campus to the university.”

(Italics mine)

“Wait a minute,” I thought. “That’s not quite how it went.”

And now I can’t let it go. Because when it comes to creating—or not creating—myths, the story of how a collection is created and the context of its donation are just as important as the interpretation of that collection by historians.

Executive Summary

Steve Jobs did not send over the vast collection of Apple’s records when he returned to the company in 1997.

Steve Jobs did not decide the new Apple he intended to build would be so forward-looking it could get rid of its museum.

Mr. Jobs did not offer Stanford University the company’s corporate archives.

Stanford did not have a signed document from Apple’s legal department within 24 hours.

(Italics mine)

Here’s the real story of how the Apple Archive ended up at Stanford.

How the Apple Archive Was Created

First of all, the Apple Archive, as Stanford calls it, is not really a traditional archives. (And yes, among archivists the convention is to call it “archives,” plural.)

A “real” archives would contain the records produced during Apple’s course of business, and they would be kept together in the order in which they were produced. A traditional executive correspondence file is a good example. But in the fast-paced startup world of Silicon Valley, it’s rare that a company keeps traditional records. So how did the Apple Archive come to be?

It begins with the Apple Library. In 1981, after Apple had been in business for 5 years, engineers in the Research & Development group decided they needed centralized research materials and services. In effect, they needed a library. So they hired a professional librarian, Monica Ertel, who built what became a world-renowned (among librarians) corporate library known simply as the Apple Library. Its overall goal was to give Apple a competitive advantage by providing information.

The Apple library remained in the R&D group with serving engineers as its priority, but it didn’t take long for other Apple groups—such as PR, Marketing, Legal and Sales—to find this resource, and they wanted historical information. So Apple librarians began collecting price lists, timelines, product data sheets, press releases, annual reports, executive speeches, policy pamphlets, news clippings—anything they deemed of historical use. The library eventually formed a history specialty group of library staff with a charter to “provide quality support to library staff and Apple employees who are seeking information about Apple’s history” and to “maintain an accurate, timely and easily accessible [historical] collection.” This “historical collection,” painstakingly collected and curated by librarians over a period of 15 years, was part of the donation to Stanford.

In addition, there was an ongoing employee-led grassroots effort to collect historical products to start a museum. In the early 1980s, an ad-hoc committee of Facilities, Records Management and the Apple Library started tracking and gathering small, informal exhibits from around the company. Employees donated documents and artifacts they thought were important, including products and prototypes. In fact, many of the historical products were gathered in an archival version of dumpster-diving where librarians collected them from hallways and trash bins when employees cleaned out their offices after being laid off.

Sadly, Apple never funded or built a museum, and eventually the Apple Library took the responsibility of storing the materials that had been gathered. We called these boxes the “museum collection.”

Together, the library’s historical collection and the museum collection were eventually donated to Stanford and formed what Stanford labeled the “Apple Archive.”

How the Apple Archive Got To Stanford

I worked as a librarian for Apple during what were probably the two most fraught years of its existence. From 1995 to 1997, Apple employees endured the ouster of CEO Mike Spindler, the appointment of board member Gil Amelio as the new CEO, the largest quarterly loss in Apple’s history, the surprise $400 million acquisition of Steve Jobs’ company, NeXT, and the return of Steve (after leaving the company in 1985), first as a “special advisor” to Amelio, who eventually resigned, and then, by September 1997, Interim CEO. All of this was accompanied by relentless layoffs (1/3 of the workforce) and the steady drumbeat of constant rumors.

In the Apple Library, we put our heads down and kept doing our jobs. But change came knocking one morning in the fall of 1997 when we received a frantic phone call from an employee in the offsite warehouse where the museum collection was stored. He had orders to clear everything out of the warehouse and shut it down, and the deadline was in 24 hours. If we wanted our boxes, we had to come and get them NOW or they would be destroyed.

Several of us jumped into a car and sped over to the warehouse where we were greeted by a scene of complete chaos: trucks, dumpsters, people rolling office furniture and equipment around a giant parking lot and everyone yelling in an atmosphere of complete panic. I got out of the car, looked around and thought, “Oh, so this is what it looks like when a company is collapsing.” We grabbed our boxes and stuffed them into a back room in the library that was also home to the HVAC system.

Then our director, Monica Ertel, received word that Steve Jobs wanted to see the library and hosted him for a tour. She started with the shelves of materials in the library proper holding thousands of technical journals, books and Apple product manuals.

“Who uses all of this?” asked Steve.

Monica answered, “The engineers use this to do research.”

Steve’s response: “They should know all that already.”

The tour was over. Several days later, moving boxes were unceremoniously dumped at the entrance to the library.

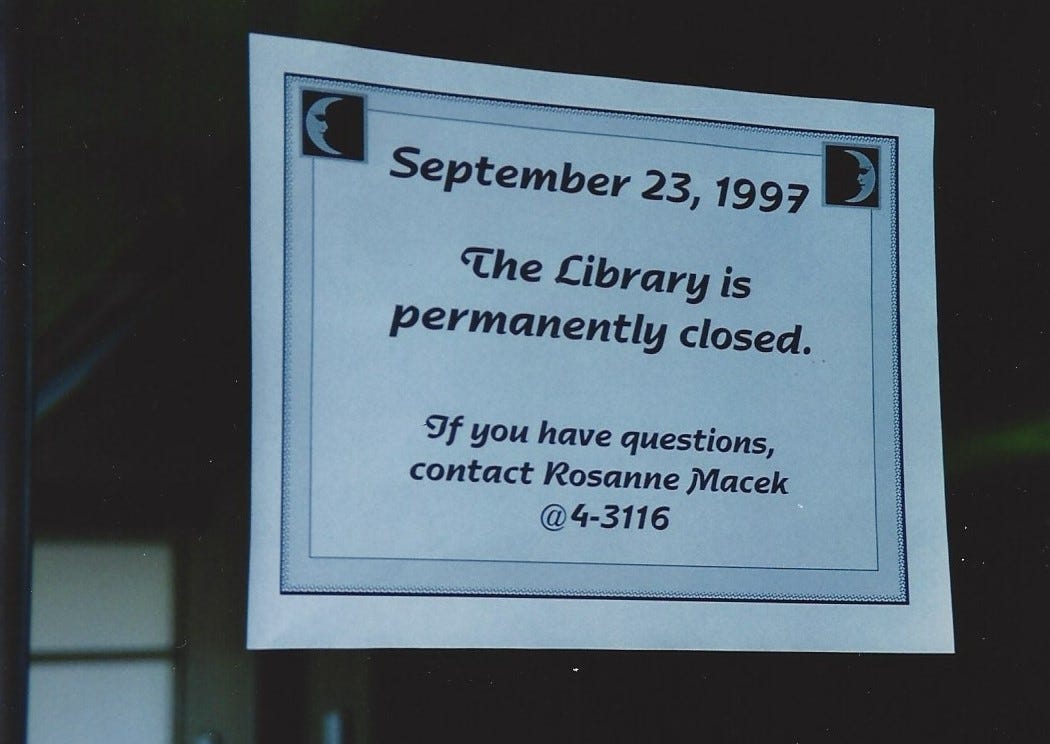

Shortly thereafter, we received official word that the Apple Library would be shut down and the entire staff laid off. By the end of September our expansive space at Infinite Loop had to be empty. We went ahead and locked the doors—permanently.

Word spread throughout Apple that the library was closing. Employees were outraged, but an email campaign to save the library proved hopeless. Condolences came in from Microsoft’s library staff, and flowers and thank you notes were left outside of the locked doors by employees.

It quickly became obvious that we could not leave the collection at Apple. No one would take it on, and even if someone did, there was no guarantee that the collection wouldn’t be destroyed later. After a couple of days of discussion, we concluded that the only way to save the Apple historical collection was to donate it.

Every corporate librarian or archivist keeps a plan to save their archives in their back pocket. We have to. Corporate archives can come under attack at any time when someone in power—a new CEO, a legal department, the consulting firm behind an acquisition, even a random IT person cleaning up servers—suddenly doesn’t like the idea of a bunch of old stuff lying around. (If you want to know how the Hewlett-Packard Company Archives was saved after enduring a major spinoff, 6 CEOs in 10 years and a company split, read my 2020 article.)

The Apple Library’s backup plan had always been to donate the collection to Stanford University’s Department of Special Collections. Stanford archivists had visited the library over the years at our request and advised us on what to include in a corporate history collection. They also explained their efforts to build a Silicon Valley Archives and let us know that our collection would always be welcome.

So once it became clear that we had to close the library and dispense with everything in it—and fast—I made the fateful phone call to the curator for Science and Technology Collections at Stanford. We had to get rid of our history collection, I told him. Was he interested?

He showed up at the Apple Library the next day with the university archivist in tow. “Wow,” I thought. “I guess this is a big deal.”

Stanford was thrilled to accept the donation. Our caveat: they had to take the entire contents of the library because we did not have time to separate out the historical materials. That meant Stanford had to take thousands of books, magazines, videotapes and actual products which normally would not be part of an archives collection. They agreed and sent over additional boxes and two of their staff. Our director managed to get a layoff extension to October 31 for the 3 Apple staffers that worked with the historical collection, myself included, and the packing began. We had one month to get everything to Stanford.

Oh, and one more thing. Stanford’s standard deed of gift had to be signed to legally donate the collection. Would it have to be signed by Steve himself? We really didn’t want to bring it to Steve’s attention.

First of all, he didn’t know the history collection existed, and secondly, he was known not to be a fan of history. And with everything going on with him being the new CEO and all, we weren’t even sure we could get him to consider it by our October 31 deadline. It certainly would not be on his list of priorities.

The task of getting the deed of gift signed fell to our library director, who still reported into R&D. We waited anxiously for weeks, continuing to pack as if everything was going to work out. Finally she managed to get her new VP, whom Steve had brought with him from NEXT, to sign off on it.

We finished on the last day we were allowed to be on campus: October 31, 1997. Halloween had always been a festive holiday at Apple—tales of Halloween parades over the years were part of Apple’s lore. Several of the long-time library employees stayed up late that last week experimenting with packages of RIT dye, then triumphantly wore one last costume that Halloween—a pink slip.

In Summary

Maybe people have just forgotten how it really happened. After all, it was 25 years ago. Shortly after the donation, however, the Stanford Daily Report captured it perfectly:

The Stanford University Libraries have acquired the museum and historical collections of Apple Computer Inc. as a gift . . .

"The Apple collections, gathered by Apple's impressive library and archival staff, reflect what amounts to the Apple crusade, as led by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Mike Markkula and John Sculley," said Michael A. Keller, Stanford university librarian, director of Academic Information Resources and publisher of HighWire Press. "Stanford is proud to have received this well-organized and complete record of the Apple story to date."

(Italics mine)

So, to circle back, when I read those quotes, why do I get so annoyed? It’s not just that they are not factual. It’s that they go beyond the facts to attribute a motive to Steve Jobs that did not exist. Steve was a hero for many things, but he did not heroically save and donate the Apple Archive—the Apple librarians did.

It’s as simple as that.

References

Jabloner, Paula and Mancini, Anna, “Corporate Archives in Silicon Valley: Building and Surviving Amid Constant Change.” Journal of Western Archives, Vol. 11, Issue 1, 2020.

Mickle, Tripp. October 22, 2022. “Who Gets the Last Word on Steve Jobs? He Might.” New York Times.

Online Archive of California, Apple Computer, Inc. records, M1007, Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

Petersen, Charles. August 8, 2021. “How I Discovered Stanford’s Jewish Quota.” Substak.com.

“A Slice of Silicon Valley History: Libraries acquire Apple collections.” Stanford Daily Report, November 19, 1997.

Anna,

This article is just so personal to me. I used to go to the library often. After having a lunch at Mac Cafe, I stopped by to browse through papers and magazines there. I could not help, since the library had so much of eye candies for me as a fun of Apple products. It seems that we were working there in the same time frame. I had worked there for three plus years starting early in 1995. Some materials in the archives are something I have gone through back then. Definitely good old days.

I was quite disappointed when I had heard that the library would be closed in 1997. Running into the library, I saw you guys were packing things up. It was sudden. I think I asked where the materials are going with no clear answer at that point. That was it. I saw the "closed" sign in another day.

Today a good friend of mine forwarded me about this article. I am so grateful that you guys saved those materials. Thank you. Thank you. Hopefully I have a chance to browse through some of them at some point.

As far as I can tell, your story is the one history should remember.

I had heard about the Apple Archive at Stanford, but I failed to look into the specifics of what this archive was prior to its donation. The Apple Library at Infinite Loop! Very cool. I went to work at Apple in 1999, so I missed out on the days of an on-site technical and historical library. That's too bad because I love this stuff. And my favorite detail of this account was, "a layoff extension to October 31 for the 3 Apple staffers that worked with the historical collection, myself included, and the packing began." That is a sure sign of a dedicated professional that sees their work as having value (and, perhaps, joy) beyond the obvious value of a salary. (I had a similar post-layoff-announcement experience, working until midnight on the last possible day to try and complete a software feature.) Kudos to the (former) archivists at Apple!